When a microscopic lab worm grows an eye-popping oddity, scientists locate the mutated gene that caused it. It’s truly interesting. Yet, more important findings, medically relevant ones, may be hiding in traits invisible to the eye, even with the best microscope.

Researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology are exposing these secrets -- micron-sized bumps and grooves -- and the intricate web of gene mutations possibly behind them in high detail. Their computational genetics work using digital optics could prove useful to understanding debilitating disorders.

“When these faint mutations come together, it gives you a ginormous boost in disease risk,” said Hang Lu, a professor who applies engineering and data science to the study of neurology.

Neurological disorder: Brain often looks normal

“If you look at psychiatric diseases, anything that is relevant to humans, what you see is not that dramatic,” Lu said. “Brains of people who had schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or autism don’t look physically very different from healthy brains. It’s not like they’re missing a chunk.”

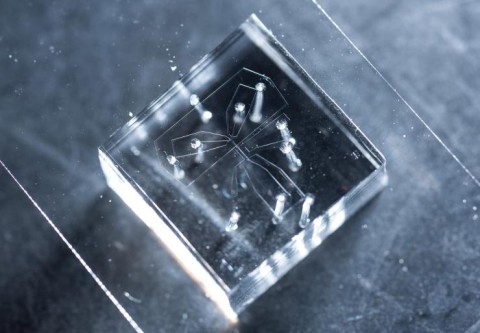

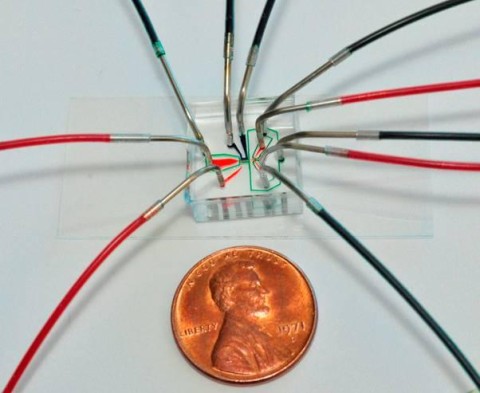

Researchers led by Lu at Georgia Tech’s School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering have developed algorithms and special microscope slide to expose previously unseen neurological nuances and intricate mutations that may be behind them. But their findings could apply as well to computational genetics research pursuing other diseases such as autoimmune disorders.

Lu and former Georgia Tech researcher Adrianna San-Miguel published their latest results on Wednesday, November 23, 2016, in the journal Nature Communications. Their research was funded by the National Institute of General Medicine, and the National Institute on Aging, both agencies of the National Institutes of Health.

Seeing dots: Computers spot subtleties

Lu has replaced the fallible human eye with a proficient computer to pin down faintest phenotypes, the geneticist’s term for physical traits based on genes. In the latest experiment, nerve proteins were marked to appear as dots on roundworms' undersides for the computer to scan.

When mutations occur, the dots can change ever so slightly. “To the naked eye, they’re just dots on a dark background,” Lu said. But the computer sees in them phenotypical shifts.

Roundworm Caenorbabditis elegans, used in the experiment, helps scientists understand what may be going on in humans, because its nerves share strong similarities with ours. Ultimately, Lu wants the insights gained in studying them to lead to localizing genetic biomarkers for diseases in humans.

Synaptic puncta: Glowing green tags

The Georgia Tech scientists narrowed their focus to synapses on a single neuron where it connects to muscles. These “synaptic puncta” were tagged with a glowing green protein to form the dots.

Some mutations did cause big shifts in dot position and size that the naked eye could actually pick up. And traditionally, forward geneticists -- geneticists who follow changes in phenotypes to see if they can find genes that cause them -- have used their eyes and microscopes to pick out such really obvious changes.

But natural limitations on human perception have introduced a bias, Lu said. Her research aims to reduce it to boost the amount of data scientists can gather.

Mutant bias: It looks funny

Here’s how the bias roughly works. Sorting mutants from non-mutants in the lab is usually tedious with the tiny worms, and that has consequences for science.

“The normal way of doing it would be to take a little platinum wire and literally go under the microscope, pick up a worm, drug it, mount it on a slide, and then you have to recover it alive, if you think it's interesting,” Lu said.

The tedium plus the limited abilities of the human eye lead researchers looking for mutations to single out worms that are markedly odd. Eye-popping phenotypes are namely likely to be caused by genotypic changes, i.e. mutations, so finding a clear phenotype is likely to lead to a successful research outcome.

Stochasticity: Not a mutant

As a result, researchers might overlook subtle samples. In addition, amassing enough of them to determine important nuances may prove too difficult to do, and quirks can get in the way, too. For example, a single weird-looking worm might not be a mutant at all.

“You can always find a ‘wildtype’ (basically normal worm) that looks nothing at all like a wildtype,” Lu said. “It’s just a crazy wildtype. Genotypically, it looks like everybody else, but phenotypically it’s so different."

Why? Because nature can be stochastic – sort of random -- and mess up an individual worm, even when there’s no mutated gene.

Phenospace: A world revealed

Looks can deceive the eye, but they’re less likely to fool a high-resolution camera connected to a computer and an algorithm that statistically examines faint variations in order to sort mutants from non-mutants.

Lu’s technique works via a transparent slide with tiny tubes that suck in one worm at a time under the computer's microscope. “Then we freeze the worm for a moment, so we can take its picture,” Lu said. “Then it unfreezes, and it’s totally okay.”

There’s a fork in the tube holding the worm. If the algorithm detects a mutant based on its synaptic puncta pattern in the image – even if this is not visible to the eye – the worm gets sucked down the first path for further study. If it isn’t a mutant, it gets sucked down the second path.

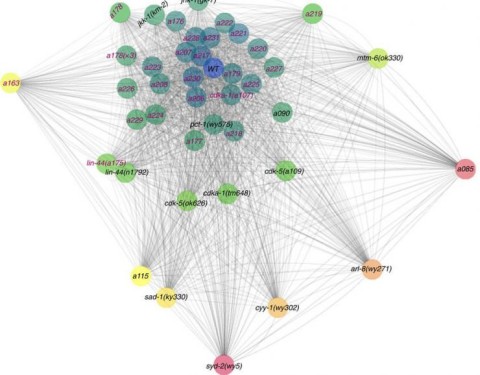

In the latest experiment, the algorithm analyzed phenotypic variations in the synaptic puncta of large worm populations. Parallel to that, the worms' genomes were analyzed to determine which phenotypical differences may be connected to mutated genes.

Then the researchers mapped out genotypes in relation to the differences in phenotypes they underpinned. What was so nuanced before that it was virtually invisible, turned out to be a large, filigree web.

Silent affliction: Poor little worm

Then there was a particularly lucky find that made for a good metaphor for the study and its potential to advance research. The scientists stumbled upon a very subtle allele – a variation of a gene caused by mutation.

The worms that had the allele were real mutants, but no one would have guessed it, because to the eye, they were completely neat and normal. They even behaved normally at first glance, and the researchers thought the computer may have sorted them out as mutants by mistake -- until a hitch turned up.

“After they swam for about 40 minutes, they got really, really weak and couldn’t swim well anymore,” Lu said. The allele seemed to be associated with some kind of neurological disorder.

“Seen as a metaphor, this is an example of how you might identify something that is relevant to a disease but incredibly subtle,” she said, “and you would never have found it using eyes and a microscope.”

The research paper was coauthored by Matthew M. Crane, Yuehui Zhao, and Patrick McGrath of Georgia Tech, and Peri Kurshan and Kang Shen of Stanford University. The research was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health (numbers R01GM088333 and K99AG046911) Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the sponsoring agency.

Writer and media contact: Ben Brumfield

Cell: (404) 660-1408

Research Communications